Understanding layouts is important for good Android application design. In this tutorial, you learn all about relative layouts, which organize user interface controls, or widgets, on the screen in relation to one another, or to their parent layout. When used correctly, relative layouts can be the powerful and flexible layout upon which many interesting Android application user interfaces can be designed.

What Is A Relative Layout?

After linear layouts, which display controls in a single row or column, relative layouts are one of the more common types of layouts used by Android user interface designers. Much like other layouts, relative layouts can be defined within XML layout resources or programmatically in the application’s Java code. The relative layout works much as its name implies: it organizes controls relative to one another, or to the parent control itself.

What does this mean? It means that child controls, such as ImageView, TextView ,and Button controls, can be placed above, below, to the left or right, of one another. Child controls can also be placed in relation to the parent (the relative layout container), including placement of controls aligned to the top, bottom, left or right edges of the layout.

Relative layout child control placement is defined using rules. These rules define how the controls within the relative layout are displayed. For the complete list of rules for relative layouts, see the Android SDK documentation for the RelativeLayout class. The associated XML attributes for use in XML resources are also defined in the documentation.

NOTE: Rules require that each child control has its id attribute set properly.

A Simple Relative Layout

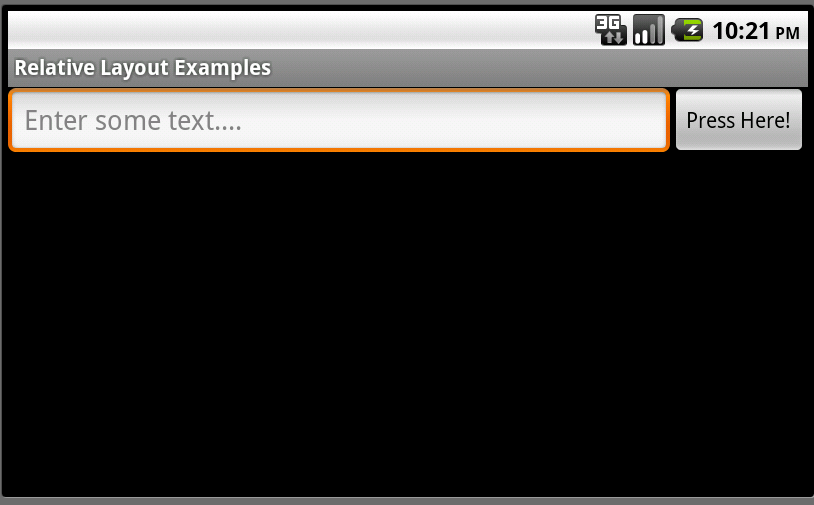

Relative layouts are best explained using an example. Let’s say we want to design a screen with an EditText control and a Button control. We want the Button to display to the right of the EditText control. Therefore, we could define a relative layout with two child controls: the EditText and the Button. The EditText control might have a rule that says: align this control in the to the left-hand side of the parent control (the layout) and to the left of a second control-a Button control. Meanwhile, the Button control might have a rule that says: align this control to the right-hand side of the parent control (the layout).

The following figures show just such a relative layout, displayed in portrait or landscape mode. The relative layout has two child controls: an EditText control and a Button control.

Defining an XML Layout Resource with a Relative Layout

The most convenient and maintainable way to design application user interfaces is by creating XML layout resources. This method greatly simplifies the UI design process, moving much of the static creation and layout of user interface controls and definition of control attributes, to the XML, instead of littering the code.

XML layout resources must be stored in the /res/layout project directory hierarchy. Let’s take a look at the relative layout introduced in the previous section. This layout resource file, aptly named /res/layout/relative.xml, is defined in XML as follows:

|

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

08

09

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

|

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<RelativeLayout

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:layout_width="fill_parent">

<EditText

android:id="@+id/EditText01"

android:hint="Enter some text..."

android:layout_alignParentLeft="true"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_toLeftOf="@+id/Button01"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"></EditText>

<Button

android:id="@+id/Button01"

android:text="Press Here!"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_alignParentRight="true"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"></Button>

</RelativeLayout>

|

Recall that, from within the Activity, only a single line of code within the onCreate() method is necessary to load and display a layout resource on the screen. If the layout resource was stored in the /res/layout/relative.xml file, that line of code would be:

setContentView(R.layout.relative);

This relative layout has its width and height set to fill the screen and three rules configured on its child controls:

- EditText01: Align to the left-hand side of the layout

- EditText01: Display to the left of Button01

- Button01: Align to the right-hand side of the layout

Defining a Relative Layout Programmatically

You can also programmatically create and configure relative layouts. This is done using the RelativeLayout class (android.widget.Relative). You’ll find the child-specific parameters in the RelativeLayout.LayoutParams class. Also, the typical layout parameters (android.view.ViewGroup.LayoutParams), such as layout_height and layout_width, as well as margin parameters (ViewGroup.MarginLayoutParams), still apply to RelativeLayout objects.

Instead of loading a layout resource directly using the setContentView() method as shown earlier, you must instead build up the screen contents in Java and then supply a parent layout object which contains all the control contents to display as child views to the setContentView() method. In this case, your parent layout would be the relative layout.

For example, the following code illustrates how to programmatically have an Activity instantiate a RelativeLayout and place a TextView and a Button control within it in its onCreate() method, much like the one shown in the previous section:

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

// setContentView(R.layout.relative);

EditText ed = new EditText(this);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams params = new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(LayoutParams.FILL_PARENT,

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

params.addRule(RelativeLayout.ALIGN_PARENT_LEFT);

// use same id as defined when adding the button

params.addRule(RelativeLayout.LEFT_OF, 1001);

ed.setLayoutParams(params);

ed.setHint("Enter some text....");

Button but1 = new Button(this);

RelativeLayout.LayoutParams params2 = new RelativeLayout.LayoutParams(LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT,

LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT);

params2.addRule(RelativeLayout.ALIGN_PARENT_RIGHT);

but1.setLayoutParams(params2);

but1.setText("Press Here!");

// give the button an id that we know

but1.setId(1001);

RelativeLayout layout1 = new RelativeLayout(this);

layout1.setLayoutParams(new LayoutParams(LayoutParams.FILL_PARENT, LayoutParams.FILL_PARENT));

layout1.addView(ed);

layout1.addView(but1);

setContentView(layout1);

}

Let’s take a closer look at the Java code listing above. First we create an EditText control as normal. We give it some RelativeLayout parameters, and then set its rules. In this case, we create two rules for the EditText control.

Next, we create a Button control and set its rule (align to the right-hand edge of the parent layout). Finally, we create a RelativeLayout object, set its parameters, add the two child controls using the addView() method and load the relative layout to display using the setContentView() method.

As you can see, the code can rapidly grow in size as more controls are added to the screen. For organization and maintainability, defining and using layouts programmatically is best left for the odd case rather than the norm.

Exploring the Important Relative Layout Properties and Attributes

Now let’s talk a bit about the attributes that help configure a relative layout and its child controls. Some specific attributes apply to relative layouts-namely the child rules, including:

- Rules for child control centering within the parent layout, including: center horizontally, center vertically, or both.

- Rules for child control alignment within the parent layout, including: align with top, bottom, left or right edge of another control.

- Rules for child control alignment in relation to other child controls, including: align with top, bottom, left or right edge.

- Rules for child control placement in relation to other child controls, including: placement to the left or right of a specific control, or above or below another control.

Also, general ViewGroup-style attributes apply to relative layouts. These include:

- Generic Layout Parameters such as layout_height (required) and layout_width (required) (class: ViewGroup.LayoutParams)

- Margin Layout Parameters such as margin_top, margin_left, margin_right and margin_bottom (class: ViewGroup. MarginLayoutParams)

- Layout Parameters such as layout_height and layout_width (class: ViewGroup.LayoutParams)

Now let’s put some of these rules into action!

Working with Layout Rules

Let’s look at a more complex screen design. For the purposes of this exercise, we will start by looking at the final screen design, and then will work backwards, discussing the relative layout features and rules used to achieve this final result.

Let’s say we want to design a screen that looks like this:

In order to design this screen using a relative layout, continue with the following steps.

Step 1: Define a Relative Layout in Your XML Resource File

First, define a relative layout in your XML resource file. Since you want this layout to control the contents of the entire screen, set its height and width attributes to fill_parent. Your XML resource file should now look something like this:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<RelativeLayout

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:layout_width="fill_parent">

</RelativeLayout>

|

Step 2: Determine Child Controls

Next, we determine what child controls we need. In this case, we need seven TextView controls (one for each color). Configure them as you normally would, setting text attributes to strings, background colors, font sizes, etc. Place each of these controls within your relative layout.

Step 3: Define Relative Layout Rules

Next, we define the rules for each child control, in order to get them to draw in the appropriate places:

- The RED TextView control has no specific settings configured. By default, this control will be drawn in the upper left-hand corner of the parent layout.

- The ORANGE TextView control is centered horizontally in the parent layout. Because all controls default to the top left-hand corner of the screen, this effectively anchors the control to the top middle edge of the parent layout.

- The YELLOW TextView control is aligned to the right-hand edge of the parent layout. Because all controls default to the top left-hand corner of the screen, this effectively anchors the control to the top right corner of the parent layout.

- The GREEN TextView control is centered vertically within the parent layout and configured to display to the left of the BLUE TextView control.

- The BLUE TextView control is aligned to the center (horizontally and vertically) of the parent control. This displays it in the middle of the screen.

- The INDIGO TextView control is centered vertically within the parent layout and configured to display to the right of the BLUE TextView control.

- The VIOLET TextView control is aligned to the bottom edge of the parent layout. It’s width is also set to fill the parent, allowing it to stretch across the bottom edge of the screen.

If you define these rules in your XML resource file, it should now look something like this:

|

001

002

003

004

005

006

007

008

009

010

011

012

013

014

015

016

017

018

019

020

021

022

023

024

025

026

027

028

029

030

031

032

033

034

035

036

037

038

039

040

041

042

043

044

045

046

047

048

049

050

051

052

053

054

055

056

057

058

059

060

061

062

063

064

065

066

067

068

069

070

071

072

073

074

075

076

077

078

079

080

081

082

083

084

085

086

087

088

089

090

091

092

093

094

095

096

097

098

099

100

101

102

|

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<RelativeLayout

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:layout_width="fill_parent">

<TextView

android:text="RED"

android:id="@+id/TextView01"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#f00"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#000"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:padding="25dp"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="ORANGE"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#ffa500"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#000"

android:id="@+id/TextView02"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_centerHorizontal="true"

android:padding="25dp"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="YELLOW"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#ffff00"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#000"

android:id="@+id/TextView03"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_alignParentRight="true"

android:padding="25dp"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="GREEN"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#0f0"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#000"

android:id="@+id/TextView04"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_toLeftOf="@+id/TextView05"

android:padding="25dp"

android:layout_centerVertical="true"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="BLUE"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#00f"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#fff"

android:id="@+id/TextView05"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_centerInParent="true"

android:layout_margin="10dp"

android:padding="25dp"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="INDIGO"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#fff"

android:id="@+id/TextView06"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_toRightOf="@+id/TextView05"

android:background="#4b0082"

android:padding="25dp"

android:layout_centerVertical="true"></TextView>

<TextView

android:text="VIOLET"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:background="#ee82ee"

android:gravity="center"

android:textColor="#000"

android:id="@+id/TextView07"

android:layout_alignParentBottom="true"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:padding="25dp"></TextView>

</RelativeLayout>

|

RelativeLayout Usage Tips

Here are some tips for working with relative layouts.

Conclusion

Android application user interfaces are defined using layouts, and relative layouts are one of the layout types used to make application screens that are both flexible and powerful. The relative layout allows child controls to be organized in relative to one another and relative to the parent (edges and centered vertically and horizontally). Once you master the rules of how relative layouts, they can be incredibly versatile, allowing you to create complex layouts without the overhead of nesting different layouts, thus improving performance.

The

The